Civilizations rise and fall on how they handle power. Some enthrone it in kings, others in councils, others in mobs. But no civilization—not Rome, not Athens, not the caliphates of the East—ever figured out how to disentangle faith from government until Christianity did. It was the first great religious system that dared to say, “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s, and unto God what is God’s.”

That sentence, spoken by a carpenter from Galilee, changed the course of political thought. It was not a call for submission to tyranny, as some have misread it. It was a declaration of boundaries—of jurisdictions. Christ’s words divided the moral from the temporal, the eternal from the administrative. He was the first to insist that divine authority and human law operate in different spheres. That principle would take seventeen centuries to blossom into what we now call the Western idea of liberty.

Early Christian communities were revolutionary in their quietness. When they moved into new lands, they didn’t demand that governments bend to their faith. They assimilated—learning the language, the customs, the dress—while keeping their worship distinct, internal, and voluntary. The pagan Romans found this baffling. Every other religion they knew was a civic religion, bound up in state ritual. The empire could tolerate any number of gods, but it could not tolerate one that refused to bow before Caesar. Christianity’s refusal to merge faith with government wasn’t defiance—it was conscience.

That was, and remains, something new under the sun.

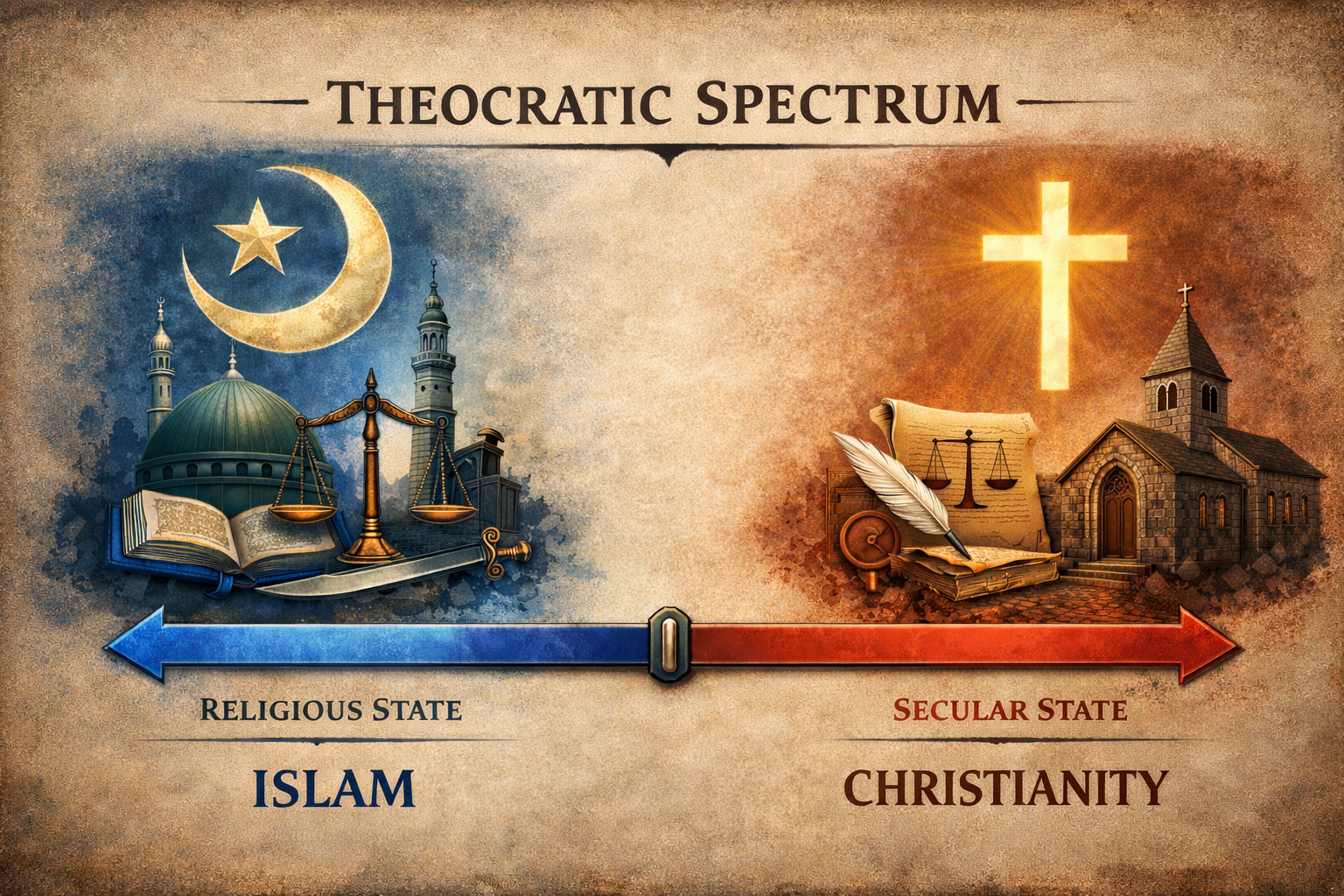

Contrast that with Islam. From its inception, Islam proclaimed itself not only a religion but a total system—a culture, a civil code, a penal code, and a political order. To be Muslim is to live under the law of Islam in all things. It recognizes no border between mosque and state, no barrier between public authority and personal faith. The idea that a government might be neutral toward religion would strike a devout Muslim jurist as absurd, even heretical. The system demands submission in every sphere: spiritual, social, and governmental.

That difference matters. It is the difference between liberty and theocracy.

When the founders of the American Republic drafted the Bill of Rights, they weren’t defending “religion” in the vague modern sense of any spiritual impulse that claims devotion. They were defending a distinctly Christian inheritance: the belief that religion belongs to the conscience of the individual, not to the coercive apparatus of the state. They were heirs to centuries of Christian argument—Aquinas, Locke, the Protestant dissenters—each insisting that faith must be freely chosen or it is no faith at all.

The Bill of Rights does not protect alien cultures masquerading as religions that demand political dominion. It protects the sacred right to worship without compelling others to do the same. It protects belief precisely because Christianity, uniquely among world religions, made belief voluntary.

And that is why America could only have been built on Christian soil.

Our founders understood what the ancients did not: that the sword cannot sanctify, that conscience cannot be legislated, and that faith, when forced, dies. The American system works because it depends on citizens who can live fully in the world while keeping their highest loyalty elsewhere—in the unseen kingdom that governs not by law, but by love.

If liberty endures, it will be because we remember that distinction.

When we forget it—when we start confusing foreign systems that merge religion and power with the faith that taught us to keep them apart—we begin to lose the very ground our freedom stands on.

Christianity taught the West how to live without tyranny of the soul.

The Bill of Rights enshrined that lesson in law.

Together, they form the only civilization in history where faith is free because power is not.

References

The Holy Bible, Matthew 22:21 — “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s; and unto God the things that are God’s.”

Tertullian, Apology (c. AD 197), Ch. 30–35 — Early Christian defense distinguishing civic duty from divine worship.

Augustine, The City of God (Book XIX) — Separation of the City of Man and the City of God as dual authorities.

Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, I-II, Q.96, Art. 2 — On the limits of human law and the supremacy of conscience.

John Locke, A Letter Concerning Toleration (1689) — Argument that faith must be voluntary and cannot be coerced by the state.

Wael B. Hallaq, An Introduction to Islamic Law (Cambridge University Press, 2009) — Discussion of Islam as an integrated legal-religious-political system.

Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (1835), Vol. I, Part II, Ch. 9 — Observation that liberty thrives under the moral discipline of Christianity.

James Madison, The Federalist Papers No. 51 — On the necessity of divided powers grounded in moral accountability before God.

George Washington, Letter to the Hebrew Congregation at Newport (1790) — Affirmation that American liberty rests on voluntary faith, not state coercion.